Haynes Publishing must be best known for their car and motorcycle maintenance manuals, but they have increasingly branched out into other territories, with recent publications including "The Human DNA Manual" and the "Milky Way Owner's Workshop Manual". In the areas of architecture and infrastructure they have published Manuals for "London Underground", "The Great Pyramid", "Hadrian's Wall" and now "Tower Bridge" (188pp, 2019, ISBN 978-1-78521-649-7).

Haynes Publishing must be best known for their car and motorcycle maintenance manuals, but they have increasingly branched out into other territories, with recent publications including "The Human DNA Manual" and the "Milky Way Owner's Workshop Manual". In the areas of architecture and infrastructure they have published Manuals for "London Underground", "The Great Pyramid", "Hadrian's Wall" and now "Tower Bridge" (188pp, 2019, ISBN 978-1-78521-649-7).It is, of course, Tower Bridge's 125th anniversary this year, and this new book by engineer John Smith joins books by Kenneth Powell and Harry Cory Wright published to mark the occasion. A comparison against the Powell book is inevitable, and although there is plenty of overlap between the two, there are some very clear differences.

Powell's book has, on the whole, the better photographs, and is a much easier read for a non-engineer, with much more detail on the context and a strong narrative surrounding those who designed and built the structure. As befits its publication by Haynes, Smith's book has far more detail on the construction work, the bridge components, and its operating technology.

The early sections of the book give a fairly comprehensive account of the somewhat tortuous process by which the bridge was eventually conceived, including the sometimes ingenious and sometimes monstrous alternative designs put forward.

The real dive into detail begins in the third chapter, documenting the eight separate contracts which were let for construction of the bridge, dividing up the works required for the piers and abutments, approach structures, metal superstructure, masonry superstructure, hydraulic machinery, paving and lighting. No client today would take this approach, retaining the entire liability for integrating a complex construction process on their own, but when the bridge was built there would have been no single contractor with the capability to do it all.

It's interesting here to see the extent to which the contract conditions used in the 1890s are very similar to those still in widespread use at the end of the 20th century. Extracts from the very first contract (for the piers and abutments) make this clear: the power of the resident engineer, payment retention, liquidated damages etc. The unrealistic timescales demanded by the client, and unrealistic prices submitted to win the work, also remain familiar today.

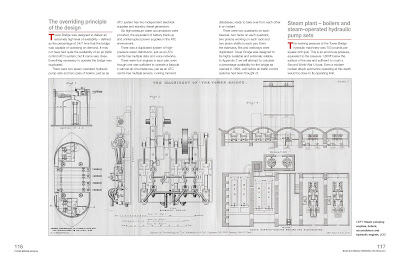

The core of the book consists of four chapters which itemise every single element of the bridge, describing them in exquisite detail and explaining just how every piece fits together. At times, the level of detail presented, with dimensions, plate thicknesses, etc, is numbing rather than interesting. For the engineering reader, there are several interesting extracts from drawings included, and the comprehensive nature of the text does mean that there appear to be no significant details left unmentioned.

There are many aspects of the bridge explained here which are essentially absent from the account in Powell's book. One example is the presence of stiffening girders concealed within the balustrades of the southern span, which ensure that water pipes carried across this span were protected against excessive movement. Another is the explanation of the arrangement of the high-level footways, the suspension bridge ties which pass through these, and the additional suspension cable added in 1960 to relieve the footway girders of the weight of those ties. These elements of the bridge are not immediately apparent to the casual visitor, but Smith's text, photographs and drawings make everything clear.

The book contains one excellent cutaway diagram showing how the components of the bridge fit together, and it's a shame there weren't more. My over-riding impression, after reading this book, is quite how complex Tower Bridge really is, and how well it merits this wealth of information. It really is an engineering masterpiece, whatever anyone may think of its architectural merits.

The book concludes with biographies of the main participants in the bridge's design and construction, and a detailed timeline of alterations and maintenance work in the period from 1894 to date. One of three appendices gives a detailed breakdown of the author's calculations of loads and forces in the bridge's key structural elements.

I couldn't, with any honesty, recommend this book to anyone who is not an engineer, but it is so detailed that it will probably remain a key reference work for Tower Bridge for the indefinite future. It is clear, thorough (sometimes too much so!) and well-illustrated throughout.