With the utterly unsurprising announcement that London's Mayor, Boris Johnson, has

given the go-ahead to the Garden Bridge project, it's perhaps worth taking stock.

I commented on this fiasco-in-the-making

last month, noting that its progress now seemed unstoppable, short of the unlikely scenario of the bridge's designers suddenly realising their own folly in an "Oh my goodness, what have I done?" moment, and deciding to quit.

This is a bridge, let's recall, which at £175m has a price tag grossly in excess of what even Donald Trump could consider reasonable (indeed, it's perhaps a surprise that Trump isn't involved, offering copious sponsorship in return for adding a couple of par-3 golf holes to the bridge). This puts it well beyond the realm of the most expensive pedestrian bridges ever built, by a considerable multiple. Having initially promised that no public funding would ever be provided, Johnson and partner-in-crime George Osborne then each offered

£30m of taxpayers cash to underwrite the job.

The rest of the funding has to come from private sponsors, and so much is required that this supposedly public oasis will be

converted twelve times a year into a private garden party for the use of its wealthy benefactors. Perhaps the capital city's poor and hungry can swim beneath the bridge on such occasions in the hope that some crumbs may spill from the lavishly decorated table. For the rest of the year, the bridge will be closed at night,

forbidden to cyclists, and

large groups (of 8 or more people) will be obliged to sneak across hoping they can dodge the inevitable CCTV hidden behind cherry blossom. For a bridge supposed to offer a great experience for the public, it won't even be a public right of way.

The bridge will ruin views along and across the Thames, including of

St Paul's Cathedral, who have joined an ever-lengthening list of people who have woken up to the bridge's adverse impacts. It's neither a very good garden (central London being already well-provided with large public parkland), nor a very useful bridge, serving no genuinely worthwhile transport need. As the Guardian has recently noted, it turns the Thames into a

playground for private fantasies, not public benefit.

Even bridge engineers, never an outspoken lot, are lining up to critique the proposals. Bridge expert Simon Bourne (not a fan of extravagance) was cited in the

New Civil Engineer magazine stating that a decent bridge could be built for just £50m, a snip compared to the bill for the Garden Bridge. That certainly sounds reasonable, given that the structurally challenging

Millennium Bridge cost about £23m just over a decade ago, and that between £26m and £40m is anticipated for the

new pedestrian bridge planned at Nine Elms (of which, more another time).

In the latest

New Civil Engineer, the Garden Bridge Trust's Paul Morrell responds to Bourne's criticism. Morrell is a Big Cheese, formerly the government's Chief Construction Adviser. However, his defence of the Garden Bridge illustrates everything which is wrong with this scheme.

Morrell says:

"I could ask for the breakdown of [Bourne's] estimate of £50m so we can learn from it", which would seem a complete waste of time given that we already have well-established benchmark costs for pedestrian bridges over the Thames. However, a failure to benchmark costs against comparable projects is entirely normal for those whose infatuation with grandiosity triumphs over common sense.

Morrell goes on to note that £50m wouldn't even cover the Garden Bridge's non-construction costs (fees, fund-raising, land, compensation and

"a long list of issues that you really do need to be working on the project to understand"). This patronising contempt for transparency is startling, but not as startling as learning that well in excess of £50m is required before you even start building the bridge - this is really quite disgraceful, but typical of a

Grand Projet culture where there is little or no meaningful challenge regarding value for money.

Of course, Morrell is a quantity surveyor,

a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. Notably, declarations of the value of the Green Bridge have been largely poetic rather than economic in nature: hello trees, hello flowers, hello sky. The government's own guidance for public investment, the

Treasury's Green Book, is routinely ignored by political promoters of the extravagant, as it requires benefits, however nebulous, to be properly evaluated and judged against the investment required. With the Garden Bridge, the net benefit may in fact be negative, and it's no surprise that no assessment of the bridge's actual value has been undertaken or published. Morrell ought to know this, so his mis-direction in justifying his project's exorbitant cost is particularly depressing.

Morrell claims:

"There is always something cheaper if that is your main aim in life, but it would not get consent, nor would it be fundable, and nor would it deliver what this bridge is designed to be: a unique celebration of British talent and creativity, of design and horticulture, of this great city - and of engineering".

Again, this is just rhetorical sleight-of-hand. We are not obliged to celebrate any of these, and certainly not to divert public money in order to do so at a time when increasing numbers of our population are unable to afford to feed their families properly. Given the other pedestrian bridges which have been built over the Thames or which are planned, it's perfectly clear that a bridge can be built which offers genuine value, at a lower price, which can get consent, and for which funding can readily be obtained, if only the political will permits. Morrell, dazzled by his association with celebrity, seems unable to see that every penny spent on the Garden Bridge folly diverts resources from transport links which would serve genuine need elsewhere in the city.

The sense of defensiveness and the deaf ear to criticism and challenge is deeply reminiscent of two other architecturally extravagant bridge follies from recent times. Sunderland's ill-fated River Wear Bridge was

also widely criticised, and as with the Garden Bridge, its backers misrepresented public opinion and ploughed on regardless, wasting millions of pounds of public money in the process. Simon Bourne was

one of the critics on that occasion, as well. Glasgow's

Neptune's Way farrago was a similar example: an absurd and rightly-criticised design which could not, in the end, be afforded, and was ditched in favour of an economic design serving the same purpose without the pointless showing off.

There is some hope that the bridge may yet be put to the sword before too much money is wasted. There's a suggestion that lawyers may seek a judicial review of the planning decisions. In addition, one of the

planning conditions imposed by Westminster is that Transport for London must underwrite the future maintenance costs of the bridge (several million pounds every year).

Opponents of the project are hoping that this may yet scupper the plans, Mayor Boris Johnson has confirmed that TfL have no intention of underwriting the maintenance.

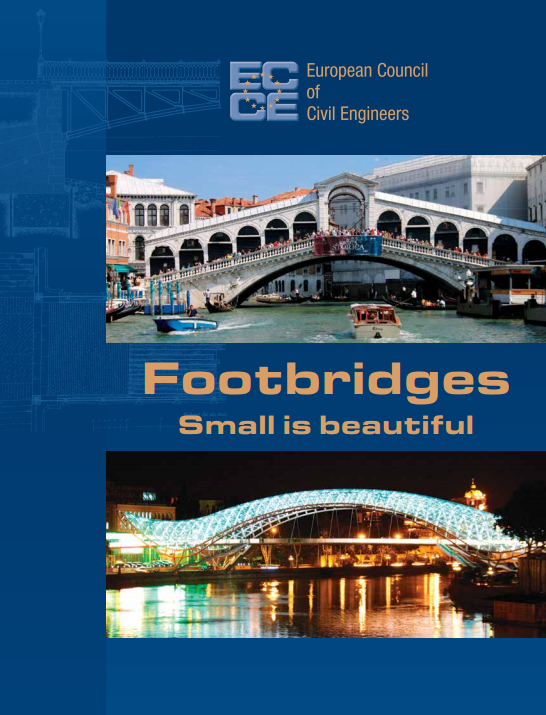

"Footbridges: Small is Beautiful" (ECCE, 414pp, 2014) is a valuable addition to this particular bookshelf. It has been produced by the European Council of Civil Engineers, an umbrella body for various national groups such as the UK's Institution of Civil Engineers. It surveys nearly 200 pedestrian bridges, with over 600 photographs, covering most of Europe as well as a bonus selection from Japan.

"Footbridges: Small is Beautiful" (ECCE, 414pp, 2014) is a valuable addition to this particular bookshelf. It has been produced by the European Council of Civil Engineers, an umbrella body for various national groups such as the UK's Institution of Civil Engineers. It surveys nearly 200 pedestrian bridges, with over 600 photographs, covering most of Europe as well as a bonus selection from Japan.